Old Growth Forests – Logging Versus Tourism on Vancouver Island

The passing of resolutions at the Union of British Columbia Municipalities (UBCM) convention last fall had been quite routine until Councillor Andy MacKinnon from Metchosin stood up. He asked that his resolution – calling for a ban on the logging of old growth forests on Vancouver Island – be moved up in priority to ensure it was discussed and voted on. From then on, things got really interesting. It quickly became apparent that a profound shift in perspective on this issue was taking place among the municipalities gathered in the room.

The logging of old growth forests in British Columbia has been a highly-charged issue, emotionally and politically, since at least the 1970s. This is particularly true on Vancouver Island, home to outstanding old growth stands of the Pacific temperate rainforest. The most well-known example is Cathedral Grove, which the highway to Port Alberni, Ucluelet, and Tofino bisects. If you’ve never experienced this remnant of an ancient Douglas-fir forest, picture walking among trees hundreds of years old, some even reaching to 800 years in age, and towering 80 metres above your head.

Vancouver Island is approximately 32,134 square kilometres (3.2 million hectares) in area. Of this, 1.9 million hectares are publicly-owned forest lands, of which the provincial government has classified approximately 840,000 hectares as old growth forests – that is, having trees over 250 years old. Hence, their estimations of the amount of remaining old growth includes high alpine and low swampy sites where the trees have little or no commercial value.

The magnificent and massive giants found on the richest growing sites have been the mainstay of the coastal forest industry from its earliest beginnings back in the late 1800s. In turn, their liquidation has brought considerable prosperity to island communities. But, decades of logging have left fewer and fewer stands intact.

With environmental groups warning that Vancouver Island’s old growth forests are on the brink of ecological and economic collapse, it’s not surprising that municipalities have begun to pay more attention to what has become an increasingly rare and valuable resource. Many are beginning to realize that they are not getting the most benefit from cutting down the last of the great stands; and, instead, are starting to see greater value in protecting them.

An Important Shift in Thinking

This represents a very significant shift in thinking among the municipalities, as historically they have been strong allies of the forest industry. According to a survey conducted by UBCM in 2015, perhaps as many as 80 percent of their membership considered their communities to be forestry dependent. But, the survey also revealed something much more important and telling. Nearly 85 percent of the respondents expressed deep frustration and anger with the lack of adequate consultation and engagement with their communities by forest companies operating around them. There were simply too many cases where forest companies cut down surrounding stands with no consultation whatsoever, leaving communities to deal with the social, economic, and ecological impacts.

Not surprisingly, forestry was a hot topic at the convention. In fact, an entire session was devoted to forest policy decision making and the need for greater community consultation. More than half of all the convention delegates crowded into the room to hear what was said and to voice their concerns. Additionally, eight of the 55 resolutions in support of existing policy dealt with the impacts of logging on local watersheds and airsheds. As might be expected, all urged the provincial government to involve local government directly in the forestry decision making – and all passed handily.

For its part, the forest industry has been caught off guard by the sudden shift in attitude toward it. The Ahousaht First Nation in Clayoquot Sound may have been the first to lead the shift. In October 2015, their chiefs called for an end to industrial scale logging in its traditional territory. Then, in April of this year, the Association of Vancouver Island and Coastal Communities (AVICC) passed a resolution at their AGM asking the provincial government to amend the Vancouver Island Land Use Plan to protect all of Vancouver Island’s remaining old growth forests found on publicly-owned land. Next came the BC Chamber of Commerce, which passed a resolution at their May convention calling for a ban on old growth logging throughout the province, wherever these trees would have greater net economic value left standing.

“It just boils down to basic math,” said Dan Hager, president of the Port Renfrew Chamber of Commerce, who sponsored the resolution. “This is not a comment about logging. It’s about economics and marketing.”

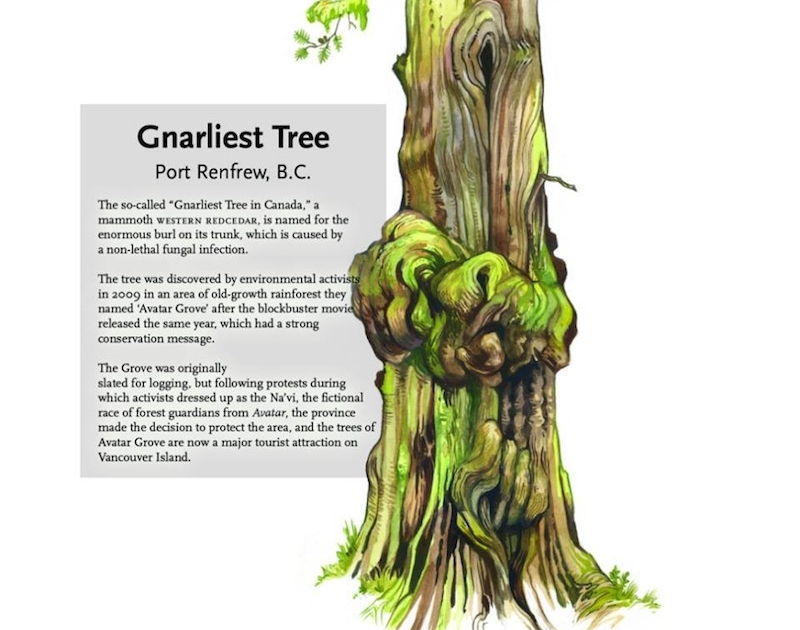

Hager’s resolution arose from personal experience and from that of other business people in the small isolated village on the outer coast of southern Vancouver Island. He and they saw a near instant and large jump in tourism in 2012 with the protection of Avatar Grove – a stunning array of massive red cedars displaying strange twisted and contorted burls. For a town that was largely established on the coat- tails of logging, but had seen the end of the glory days, the steady, year-round flow of tourists keen on seeing big trees is a huge shot in the arm for the community.

Hager figures that the demand for accommodation alone has grown by as much as 75 to 100 percent over the past three to four years.

A Larger Scale

With this kind of traction, it was probably inevitable for a similar resolution to be presented at the UBCM convention and that it was sponsored by the Municipality of Metchosin’s Councillor Andy MacKinnon, who had put forward the initial resolution to the AVICC a few months earlier.

It was after voting on the first block of resolutions when Councillor MacKinnon stepped to a floor microphone and asked that his resolution calling for a ban on the logging of old growth forests on Vancouver Island be moved up in priority to ensure it would be debated and voted on.

At the moment, it had been listed as the very last resolution with many others stacked in front of it.

At first, he was told that this wasn’t possible; but then, the chair changed his mind and said this was only possible if the members voted 60 percent in favour of doing so. A vote was quickly held, demonstrating that a large majority supported the escalation in priority. When it came to his turn to speak his resolution, MacKinnon lost no time in calling into question the facts and figures provided by the provincial government and used by the UBCM’s resolution committee to support its recommendation that his resolution be viewed as strictly a regional issue and dealt with at that level.

Drawing on his near 30 years of experience within the Ministry of Forests, MacKinnon suggested that the figures were inflated and not based on any research that he knew of. The reality, he said, was vastly different as any look at satellite photos of southern Vancouver Island makes so startlingly clear. There are no stands of old growth forests on productive sites left on the eastern side of the island, and only a few remain on the more rugged and sparsely populated western side.

During the following debate, three or four members spoke against the resolution. Councillor Charlie Corneld from Campbell River was among them. He reminded everyone that many communities on Vancouver Island were still dependent on the logging of old growth. But, the angriest was Councillor Al Siebring from North Cowichan who fumed: “We wonder why so many of the resolutions we send to senior levels of government get blown off. It’s because we’re not sticking to our knitting.” He made it abundantly clear that he felt that the issue of old growth logging was outside the municipal mandate and shouldn’t be endorsed by the UBCM.

Nevertheless, it was abundantly clear that an overwhelming majority of members supported the resolution, which was well demonstrated in the following vote.

An Ongoing Battle

The passing of this resolution (and the others like it) has delivered a hard gut punch to the forest industry on Vancouver Island. Historically and generally speaking, the members of the UBCM and B.C. Chamber of Commerce have been allies of the industry. From the industry’s point of view, the problem was simply that these people just didn’t have all the “real” facts and needed to be educated. The industry maintains that 55 percent of the B.C.’s coastal old growth forests are already protected, and that this percentage will only increase over time owing to good conservation practices outside of protected areas. MacKinnon disagrees, pointing out that much of what has been protected are high alpine forests of no interest to the forest industry and that less than six percent of Vancouver Island’s old growth forests found on productive growing sites remain. Even those are being cut down at a rate of about 9,000 hectares a year. He notes that it’s just a matter of time before the industry runs out of big trees and is forced to make the transition to harvesting and milling second growth stands of smaller trees. A ban on logging old growth forests on Vancouver Island would speed the transition along.

“Although it wasn’t specially mentioned in the resolution,” he points out, “the idea of natural capital and eco- system services is rejected in the ‘where as’ clauses. At the time, the Gibsons’s approach to natural capital wasn’t widely known. They had a workshop on it as part of the convention, which I attended, and I came away really admiring what they are doing. I think what was going through people’s minds, as they were overwhelmingly supporting the resolution, I’m sure they were thinking about their communities and there is a strong interest in the idea of natural capital among them. So, that discussion is going to continue.”

For the forest industry and provincial government, this discussion likely means more trouble with recalcitrant municipalities determined to protect and maintain natural ecosystems that provide so many benefits to their communities.