Forests Can Only Fight Climate Change if We Become Better Stewards

After a 10-year “climate action pause,” Canada is back at the international table. Though expectations are high that the new government will work to end our dependence on fossil fuels and speed up the transition to renewable energy, there has been little discussion about the importance of and threats to our forests in the fight against global warming.

Despite ongoing deforestation and degradation, the world's forests absorb about one quarter of our emissions. This is one of the key reasons why global warming isn't already much worse. Unfortunately, as a result of poor forest management and climate-driven impacts like droughts, insects and fires, many of our forests are now absorbing less carbon than they are releasing into the atmosphere. Since forests store 340 billion tonnes of carbon (equivalent to about 34 years of annual global emissions), we cannot afford to lose these valuable carbon sinks through continued mismanagement.

Before humans started to alter natural landscapes in a significant way, half our planet's land mass was forested. Today, only about 30 per cent remains covered by forest. As a result of this deforestation, the majority of which has occurred in the last several decades, the world has lost a significant part of its natural environment, species habitats and natural carbon sinks.

A Nature study released earlier this year showed for the first time, how many trees still grow on earth. Canada is home to over one tenth of the planet's 3 trillion trees — 318 billion trees — and no other country has more trees per capita (8,953 per person).

Arguably, Canadian citizens and their governments have a global responsibility to be good stewards of our forests. Canada's forests are vast and contain outstanding ecological values, and large tracts remain undisturbed from industrial activity. Approximately 348 million hectares (about 35 per cent of Canada's landmass) are forested. Only Russia and Brazil have more forest area, but both countries have less intact forest, greater economic challenges and much bigger populations than Canada.

Canada's two most important forest ecosystems are found in the taiga and the temperate zone. The taiga covers more area than any other forest type, while temperate rainforests grow the tallest trees on the planet. The boreal forest region is home to countless migratory songbirds and some of the world's largest populations of northern mammals, including caribou, bear and wolves.

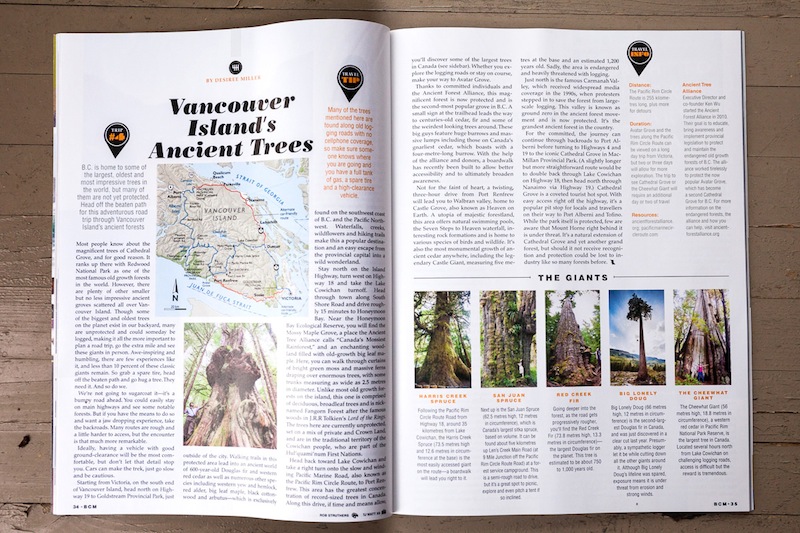

The largest remaining intact tracts of temperate rainforest on the planet are found along the Pacific Coast of British Columbia and provide a refuge for species which have declined across their historical range, such as grizzly bears and Pacific salmon.

Forgetting stewardship

But despite its wealth and relatively small population, forest conservation and stewardship have been neglected in many regions of Canada. While approximately 90 per cent of Canada's forests are on public land, logging rights for most forests of economic value have been given to large corporations, many of which are operating under weak government regulation, monitoring and enforcement. Furthermore, climate change-driven impacts, such as wildfires and the mountain pine beetle outbreak in Western Canada, are worsening.

For Canada, the gradual process of forest degradation (the long-term loss of forest structure from industrial logging or frequent fire) is a much greater problem than deforestation (the complete loss of forest). According to analysis by Greenpeace and the University of Maryland, globally over 100 million hectares of intact forests were lost to degradation from 2000 to 2013 (eight per cent of what remained at the beginning of the millennium). Shockingly, Canada contributed 21 per cent of this loss, more than any other country.

The largest driver of forest degradation in Canada is logging. In 2012, approximately 600,000 hectares of forests were logged in Canada (in contrast, deforestation, e.g. as a result of urban growth was 45,000 hectares in 2012). In Alberta's tarsands region, industrial development and forest fires have cleared or degraded nearly 800,000 hectares between 2000 and 2013 (5.5 per cent of the region's land area).

Meanwhile, Canada has set aside only 8.5 per cent of its land in permanent protected areas (12.2 per cent if interim protection is included). But scientists recommend that half of the landmass should be set aside to protect species habitat and safeguard ecological services, and there is a significant gap to meet the goal agreed to in the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity to set aside 17 per cent of the world's terrestrial ecosystems by 2020.

One model of progress

One notable model for conservation progress is B.C.'s Great Bear Rainforest region. In 2006, after years of conflict and negotiations, the provincial government, First Nations, a group of logging companies and a coalition of environmental organizations endorsed the Great Bear Rainforest Agreements. The goal is to achieve ecological integrity, economic activity building on conservation and shared decision-making between the provincial government and First Nations. Once fully implemented (expected before the end of the year), 85 per cent of the region's rainforest will be set aside under Ecosystem-Based Management, through a combination of protected areas and stricter logging regulations.

South of the Great Bear Rainforest, in Clayoquot Sound, there is new hope that a lasting conservation solution can be found for the remaining unprotected intact rainforest valleys on Vancouver Island, particularly since the Ahousaht First Nation announced in October an end to industrial logging in their territory, spanning the majority of this region.

However, much of the productive old-growth rainforest has already been logged in the southern part of the B.C. coast and logging continues in some of the last remaining intact areas on Vancouver Island, such as the Walbran Valley, despite opposition. Logging of these rainforests is particularly concerning because old-growth stores record high amounts of carbon per hectare, accumulated over thousands of years, and steadily sequesters more carbon from the atmosphere. Clearcutting old-growth releases enormous amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Tree power!

Increasing protection of old-growth forest and improving forest management could quickly reduce carbon losses from forests, particularly in B.C.'s forests with their very high carbon storage. A recent Sierra Club B.C. report found that in B.C. forests as a whole have been a net emitter of carbon over a full decade (2003-2012). This contrasts to their historic role capturing large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere. While the mountain pine beetle and more wildfires have tipped the balance, our analysis shows that logging practices remain the biggest factor contributing to B.C.'s forest carbon emissions.

Canada's vast intact forest landscapes present an outstanding potential and responsibility to contribute to global climate solutions. Canada should heed the call of scientists and set aside 50 per cent of the range of Canada's boreal forest ecosystems. A similar level of protection is needed in other regions of the country with large intact ecosystems to protect biodiversity and carbon values.

Climate-harming fossil fuel subsidies should be transferred to increase forest conservation, improved forest management and support value-added forest products manufacturing and other sectors of the low-carbon economy. This would increase jobs per unit of wood cut and enable modern logging practices, such as selective logging, reducing wood waste, eliminating slash burning and growing older trees. Global warming means that we need a paradigm shift to end Canada's large-scale land degradation and ensure that our forests stop losing carbon. In short, there is no climate-friendly wood product without forest-friendly forestry.

Thirty-five million Canadians, half a per cent of the world's population, are stewards of 10 per cent of the world's forests, one-third of the planet's fragile boreal forest and one-quarter of the remaining intact forests on Earth. There is no other nation whose citizens could contribute more to saving our forests.

Read more: https://thetyee.ca/Opinion/2015/12/04/Become-Better-Forest-Stewards/